Appalachian Trail Series, Part 3: Trail Clubs, Shelters, and How the A.T. Is Supported

Words by Michele Underwood | Photos by Michele and other contributors

A forested stretch of the Appalachian Trail in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

In Part 1 of this series, I looked at the big picture—the Appalachian Mountains, Benton MacKaye’s early vision, and how a rough idea turned into a real trail. In Part 2, I focused on the modern Appalachian Trail—where it starts and ends, the states it crosses, and how the route flows from Georgia to Maine. This post zooms in on what makes the trail work day to day.

The Appalachian Trail isn’t just a footpath. It’s a coordinated system of organizations, volunteers, shelters, and campsites that allows millions of people to hike it while keeping the corridor protected.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) is the nonprofit organization responsible for overseeing the entire trail. It doesn’t maintain every mile directly, but it coordinates the people and agencies that do.

ATC works with:

More than 30 local and regional Appalachian Trail clubs

Federal land managers like the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service

State parks and forests

Thousands of volunteers who maintain the trail, shelters, and signage

ATC sets standards, protects the trail corridor, manages long-term planning, and helps ensure the A.T. remains a continuous footpath from Springer Mountain to Katahdin. For hikers, planners, and anyone curious about how the trail works, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s website is the best place to find official information on regulations, trail updates, and long-distance hiking registration.

Appalachian Trail clubs and section stewardship

The Appalachian Trail is divided into sections, with each stretch assigned to a specific trail club. These clubs are typically regional hiking organizations that take responsibility for maintaining their miles.

Trail clubs are responsible for:

Clearing blowdowns and trimming overgrowth

Maintaining tread, drainage, and stonework

Repainting and maintaining white blazes

Repairing shelters, privies, and campsites

Monitoring erosion and reroutes

Every mile of the Appalachian Trail has a club behind it.

Some of the better-known Appalachian Trail clubs include:

Most hikers never meet the people who maintain the trail, but the trail exists because they’re out there year-round.

Appalachian Trail Shelters, Campsites, and Mileage — Interactive Map

Use this official map to explore shelters, designated campsites, trail mileage, and land management boundaries along the Appalachian Trail. It’s handy for section hikers who want to see spacing between shelters and how different parts of the trail are managed.

(Map courtesy of the National Park Service and Appalachian Trail Conservancy.)

Registration, permits, and sign-ins

Amicalola Falls State Park visitor center, where many northbound Appalachian Trail hikers sign in before starting the Approach Trail.

Not every section of the Appalachian Trail requires registration, but some areas do—especially places with high use or sensitive environments.

Common examples include:

Amicalola Falls State Park: Many northbound hikers sign in at the visitor center before starting the Approach Trail.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Thru-hikers and section hikers must obtain permits to camp within the park.

Baxter State Park: Katahdin access is tightly managed with seasonal rules, quotas, and weather-related closures.

These systems help land managers protect the trail and plan maintenance—they aren’t meant to limit who can hike it.

Registration and permits exist for a few practical reasons. They help land managers understand how many people use the trail, which sections are most impacted, and when maintenance or seasonal restrictions are needed. In heavily used or fragile areas, registration also helps prevent overcrowding, protects campsites and water sources, and ensures hikers are following park-specific rules designed to keep the trail open long-term.

For hikers interested in the official Appalachian Trail hiker registration—and the iconic hang tag or patch that often ends up clipped to a pack—timing matters. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy asks thru-hikers and long-distance hikers to register shortly before starting their hike, not months in advance. Registration typically opens for the upcoming season in winter, and hikers are encouraged to register once their start window is firm. This helps ATC manage use at the southern terminus during peak season and ensures the registration reflects who is actually on the trail.

Appalachian Trail hiker registration hang tag, often clipped to a pack by thru-hikers and long-distance hikers.

Pro tip: Many hikers go by a trail name—a nickname earned or chosen early on the A.T. You don’t need one to start, but you may be asked for it when signing registers, talking with other hikers, or filling out forms. It’s worth having something in mind, even if it changes as the hike goes on.

Shelters and designated campsites

One of the defining features of the Appalachian Trail is its shelter system.

Along the trail, you’ll find:

Three-sided shelters, usually spaced a day’s hike apart

Designated tent sites near shelters or water sources

Privies, typically composting or pit-style

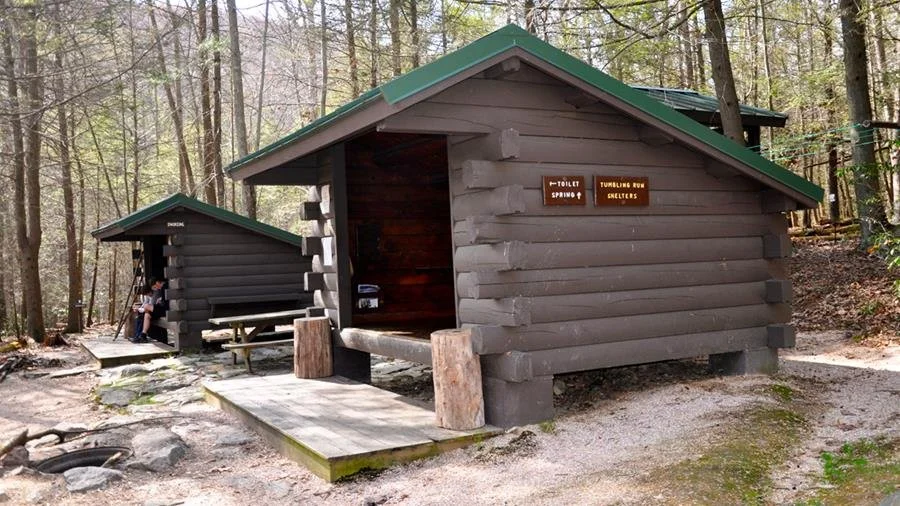

A classic three-sided Appalachian Trail shelter, spaced roughly a day’s hike apart along the trail.

Shelters are first-come, first-served and aren’t guaranteed lodging, but they shape how many people experience the A.T.—especially first-time and section hikers.

In some areas, camping is restricted to shelters and designated sites to reduce impact on surrounding land.

Appalachian Trail shelters and designated campsite area, including nearby privy and water access.

Hikers typically know where shelters and campsites are located before they start by using official Appalachian Trail maps and guides, the A.T. Guide (often called the AWOL Guide), and digital tools like FarOut. These resources show mileages between shelters, water sources, and campsites, making it easier to plan daily distances and overnight stops ahead of time.

Trail towns and resupply points

Between trail sections are trail towns—small communities that support hikers with food, lodging, and transportation.

Some towns sit directly on the trail. Others require a short hitch or shuttle. These stops allow hikers to resupply, rest, and reset before heading back into the woods.

Trail towns are part of the A.T.’s culture and economy, linking the footpath to the communities it passes through.

Why this system matters

Every white blaze, shelter roof, and cleared switchback exists because someone put time into caring for the trail.

If you find this system worth supporting, you can donate to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy to help fund trail maintenance, land protection, and volunteer programs that keep the A.T. open and protected for future hikers.

In the next part of this series, I’ll get into what it actually looks like to hike the Appalachian Trail—thru-hikes, section hikes, and shorter trips that still feel like real A.T. time.

Michele Underwood writes Overland Girl, in which she shares the gear she uses on her trips—from the Northwoods of Wisconsin to the Ozarks. She values quality and craftsmanship in everything she buys—from outdoor gear to everyday clothes and furniture. Her choices may seem expensive to some, but she believes in buying less and buying better. Longevity matters, both in terms of function and style. Her couch is five years old and still sold at Design Within Reach—that's the kind of timelessness she looks for. Some of the links in this review are affiliate links, which means she may earn a small commission if you buy through them. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, and it helps support her work. She only recommends gear she’d bring herself.