Appalachian Trail Series, Part 1: The Mountains and the Big Idea

How Appalachian Trail history

shapes the trail today

Words by Michele Underwood | Photos by Michele and other contributors

“Maine to Georgia” marker at the Appalachian Trail approach trail entrance in Amicalola Falls State Park—the gateway to the southern terminus.

I was recently mountain biking close to the southern terminus of the Appalachian Trail. I’ve wanted to step foot on this trail for years, and that day I finally got close enough to start paying attention. I learned there’s even a section of trail before you reach the “official” start, and I met two hikers—a father and daughter—walking out after finishing the entire thing.

This trip is what finally pushed me to write this series. The Appalachian Trail has an incredible story, and I want to tell it piece by piece. By the end, you might find yourself planning to hike part of this trail—or all of it. I plan to.

Before getting into specific sections or how to hike the A.T., it helps to zoom out. First to the Appalachian Mountains as a whole, then to the idea that pulled a single footpath across that spine.

Appalachian Mountains overview

Rolling ridgelines in the southern Appalachians—rounded, forested mountains that set the stage for the Appalachian Trail. Photo: Clark Wilson via Unsplash.

The Appalachian Mountains run for about 2,050 miles down the eastern side of North America, from the edge of Newfoundland all the way to central Alabama. This range is old—these peaks started forming more than 300 million years ago and have eroded over time into rounded summits and long, forested ridges.

A few big anchors help frame the picture:

The highest point in the Appalachians is Mount Mitchell in North Carolina, at 6,684 feet, and it’s also the highest summit east of the Mississippi River.

The southern end of the range fades into the hills of Alabama, where ridges line up above the Coosa and Talladega country.

To the north, the mountains carry on through New England and into Atlantic Canada.

For people who live along this belt, the Appalachians are not just a skyline. They hold small mountain towns, coal and timber history, farms in the valleys, and a web of local trails. I mountain bike near the southern end of these mountains in Birmingham, Alabama. The Pinhoti Trail picks up that same Appalachian spine and carries it north. The future Appalachian Trail was always going to live on these ridges—and trails like the Pinhoti are part of that same story further south.

Early vision for an Appalachian Trail

By the early 1900s, industrial growth along the East Coast had pulled many people into dense, noisy cities. At the same time, railroads and logging roads cut deep into the mountains. Logging, mining, and mill towns popped up in pockets of forest. You can still see the marks of that era today in old road cuts and grades that now form parts of hiking and mountain bike trail systems—like sections of the Pinhoti in North Georgia.

Outdoor clubs were already building regional trails in New England and the Mid-Atlantic. Hikers and planners started to talk about stitching some of those paths together into something bigger—a continuous way through the mountains that sat just beyond the city edge.

The stage was set for one bold idea.

Benton MacKaye and the first Appalachian Trail plan

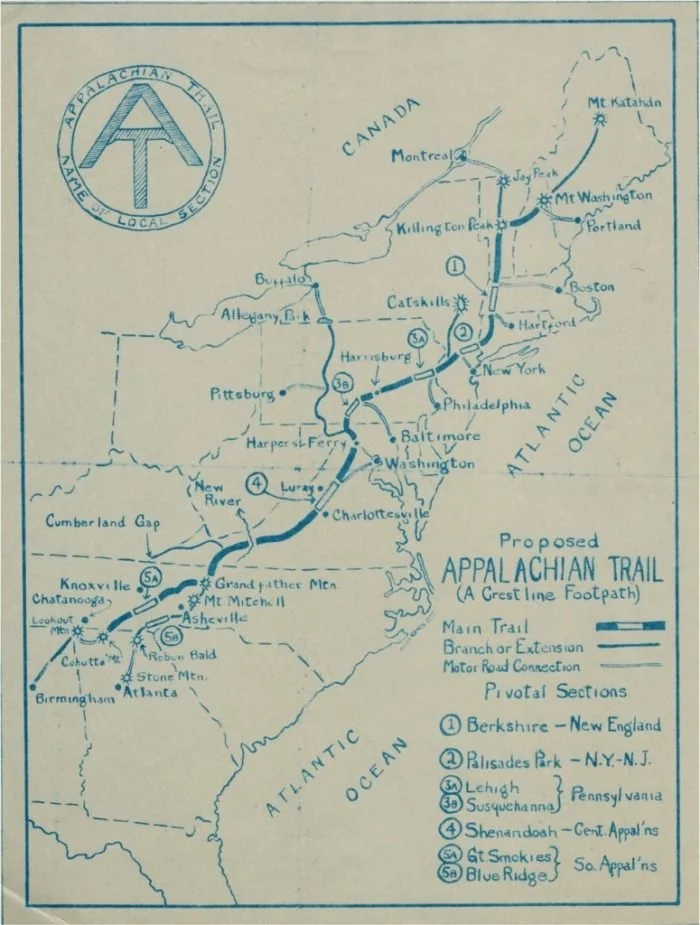

Early 1920s map of the proposed Appalachian Trail drawn by Benton MacKaye. The blue line marks his original idea for a crestline footpath along the Appalachian Mountains from Georgia to Maine.

Image courtesy of [Appalachian Trail Conservancy / Smithsonian Institution

In 1921, a forester and planner named Benton MacKaye published an essay called “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning.” He pictured a network of camps and small communities in the mountains, linked by one long footpath that followed the Appalachian crest.

MacKaye’s vision leaned on a few key points:

The trail would run from the highest peak in New England down to the highest peak in the southern Appalachians.

It would not be only a hiking path. It would be part of a larger plan for healthier living, outdoor work, and community in the mountains.

City residents would have a place to step away from crowded, industrial life and spend time on the ridges instead.

The idea landed at just the right time. Hiking clubs, conservation groups, and park planners were already active up and down the range. MacKaye’s essay gave them a shared target.

Building the early Appalachian Trail

Within a few years, local groups started turning MacKaye’s lines on paper into dirt underfoot.

In 1923, the first A.T.-specific section opened at Bear Mountain in New York.

In 1925, volunteers and officials formed the Appalachian Trail Conference (now the Appalachian Trail Conservancy) to coordinate work across states and push toward a continuous trail.

A modern view of the Appalachian Trail on Bear Mountain, New York—the area where the first A.T.-specific section opened in 1923. Photo: Gary Miotla via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Another key figure stepped in: Myron Avery. Where MacKaye had the big-picture vision, Avery was the one who obsessed over exact routes, mileages, and blazes. Under his leadership, state trail clubs, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and thousands of volunteers cut tread, built shelters, and connected the gaps.

By August 1937, crews finished the last missing link in Maine and the Appalachian Trail existed as one continuous footpath through the mountains.

From regional footpath to National Scenic Trail

For a while, the A.T. crossed long stretches of private land, with only loose protection. The route also shifted to make room for new parkways and development. The focus slowly moved from “build the trail” to “protect the corridor around the trail.”

A major milestone came in 1968, when Congress passed the National Trails System Act and designated the Appalachian Trail as the country’s first National Scenic Trail, alongside the new Pacific Crest Trail.

Today:

The A.T. runs about 2,197 miles between Springer Mountain, Georgia, and Katahdin in Maine, passing through 14 states.

The trail is one of the longest hiking-only footpaths in the world, with millions of visitors each year.

More than 99 percent of the route is now protected by public ownership or permanent rights-of-way.

It still relies on a volunteer army. Local clubs and partners maintain tread, shelters, and signage under the umbrella of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and federal land agencies.

Appalachian Trail history timeline

For easy reference inside this series:

1921 – Benton MacKaye publishes his Appalachian Trail proposal.

1923 – First marked section opens in New York’s Harriman–Bear Mountain area.

1925 – Appalachian Trail Conference is formed to coordinate the build-out.

1937 – Final gap is closed in Maine; the trail becomes a continuous route.

1968 – National Trails System Act designates the Appalachian Trail as the first National Scenic Trail.

2020s – Official length sits around 2,197 miles, with minor changes almost every year as sections are relocated or refined.

How Appalachian Trail history shapes the trail today

On the Appalachian Trail, the route is marked by small white rectangles of paint on trees, posts, and rocks—called white blazes. Knowing this backstory changes how I see them. Each blaze isn’t just paint; it represents decades of planning, land protection, and volunteer work that made this long trail possible.

A classic white blaze marking the Appalachian Trail on a tree in the Delaware Water Gap, Pennsylvania. Photo: C. G. P. Grey via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Every time the trail swings past an overlook, drops to a road crossing, or threads a narrow ridge, there is a century of planning, negotiation, and volunteer work behind that line. The A.T. is not just a long hike. It is a living project that ties together geology, small towns, conservation, and outdoor culture along the Appalachian Mountains.

This first post lays the foundation. Next in the series, I’ll move into the modern Appalachian Trail—where it starts and ends, the states it crosses, and how the trail flows from Georgia to Maine.

Michele Underwood writes Overland Girl, where she shares gear she uses on real trips—from the Northwoods of Wisconsin to the Ozarks. She values quality and craftsmanship in everything she buys—from outdoor gear to everyday clothes and furniture. Her choices may seem expensive to some, but she believes in buying less and buying better. Longevity matters, both in terms of function and style. Her couch is five years old and still sold at Design Within Reach—that's the kind of timelessness she looks for. Some of the links in this review are affiliate links, which means she may earn a small commission if you buy through them. It doesn’t cost you anything extra, and it helps support her work. She only recommends gear she’d bring herself.